создание топика, блога

Записная книжка сисадмина → Employ Five Fundamental Principles to Produce a SOLID, Secure Network

This paper will present a strategy that, if implemented, will improve confidence that all necessary precautions in establishing a secure network have been taken.

Mark Ciampa, author of several network security textbooks, states: “Although you need many defenses to withstand attacks, you base these defenses on a few fundamental security principles: protecting systems by layering, limiting, diversity, obscurity, and simplicity” (Ciampa, 2005).

The author of this paper devised the acronym SOLID (Simplicity, Obscurity, Layering, Impeding, Diversity) from those principles to be used as an aid in designing, developing, and deploying a security strategy to confidently build a SOLID, secure network. The definition of the term solid includes “of good substantial quality or kind,” “thoroughly dependable,” “reliable,” and “serious in purpose or character” (Merriam-Webster, 2004). A network security administrator strives for a solid, impenetrable network. The acronym SOLID will serve as a model throughout the analysis, development, and implementation of a security plan. When reviewing the security strategies, the SOLID principles may be used in a checklist to determine the degree to which each principle has been applied in the security plan.

FUNDAMENTAL SECURITY PRINCIPLES

Examining the five network security principles individually will illustrate the importance of each. As each principle is explained throughout this article, the reader should strive to recognize strategies that relate directly to the network system being managed.

Simplicity

Simplicity is representative of how easy, or complex, it is to access the network. From the user’s perspective, the internal policies and procedures should not be too difficult to manage, thus preventing users from being productive in their daily tasks. In contrast, the network should be complex enough to ward off intruders. Network administrators must find the correct balance (unique to each situation) between blocking unwanted and unwarranted access to the network and providing the resources necessary to the authorized users of the network. “There is no such thing as ‘complete security’ in a usable system. Consequently, it is important to concentrate on reducing risk, but not waste resources trying to eliminate it completely. Such a pragmatic mindset provides a fighting chance to achieve fairly good security while still allowing productivity” (Avolio, 2009).

Establishing policies is critical to a secure network. One network security white paper on “best practices” states to create usage policy statements that outline users’ roles and responsibilities with regard to security: “This document should provide the general user community with an understanding of the security policy, its purpose, guidelines for improving their security practices, and definitions of their security responsibilities. If your company has identified specific actions that could result in punitive or disciplinary actions against an employee, these actions and how to avoid them should be clearly articulated in this document” (Cisco Systems, 2009). Education on the use of the system is extremely vital to the success of policy implementation. Another best practices article on wireless network security supports the same: “… develop institution-wide policies with detailed procedures …” and “conduct regular security awareness and training sessions for both systems administrators and users” (Kennedy, 2003).

An additional strategy that must be considered when implementing the simplicity principle pertains to default settings of hardware and software. In this case, the simplest thing to do is apply all of the default settings when installing new equipment or operating system and application software upgrades, but this is not necessarily done in the best interest of developing a secure network. Default settings often include password, encryption, and authorization settings that are known by anyone familiar with the same hardware or software. Therefore, though it takes a great deal of effort on the part of the technician to manage the new or improved system, changing many of those default settings will protect the system from hackers (Kennedy, 2003).

The SOLID principle of simplicity requires a security strategy responsive to all system functions. An unrestricted environment may allow faster processing but is not practical when handling confidential data. Hardening an operating system to the extent that the user is frustrated with each task submitted is also not a practical solution. A checks and balances system must be in place to weigh the simplicity and complexity of the network. Security measures should be taken that will not jeopardize user productivity.

Obscurity

WordNet defines obscurity as “the quality of being unclear or abstruse and hard to understand,” “not well known,” and “the state of being indistinct or indefinite for lack of adequate illumination” (Princeton, 2006). Obscurity may also be considered the “hidden” aspects of network security. Security by obscurity… represents one of the truly controversial aspects of security. You will often see mocking references to people whose efforts are dismissed as ‘just security by obscurity’” (Johansson & Grimes, 2008). Obscurity is used to lessen a risk or vulnerability by concealing the attack vector, thereby applying a reinforced measure of security to the system.

Examples of obscurity include renaming the administrator account to deter automated attacks and installing honeypots to act as decoys, enticing hackers away from the systems containing critical data. For a wireless network, changing the default Service Set Identifier (SSID) set by the manufacturer is important. The default SSID for Cisco wireless routers is “tsunami,” and the default SSID for Linksys wireless routers is “Iinksys.” A complex SSID naming convention should be defined and implemented to avoid easy access by an automated attack or an unauthorized user. The serious hacker may still be able to find a way around these security measures, but it does make the effort more difficult.

Included in obscurity should also be the avoidance of clear patterns of behavior, even to the point of random time settings for synchronizing systems across the network Consider a communication strategy used by the military in which a continuous signal of spurious transmissions is used to reduce the enemy’s detection of a serious communication when it is transmitted. Though spread spectrum techniques do not directly apply to the commercial domain, the implementation of clear behavioral patterns should be avoided.

The implementation of obscurity into the security plan is only one line of defense — not the line of defense — and is not to be measured but rather used as an early warning sign of exploitation. When such a barrier is breached, a potential and likelihood of a full-scale attack is amplified. This strategy may take some effort, but it is a principle that merits thoughtful consideration and periodic review to preserve the integrity and defense of the network.

Layering

Building layers of defense to protect digital assets is critical. Layering is implemented in the physical security plan as well as policy and administration. “Protecting your proprietary information does not require dozens of specialized solutions or unlimited funds. With an understanding of the overall problem, creating both a strategic and tactical security plan can be a straightforward exercise” (Ashley, 2006).

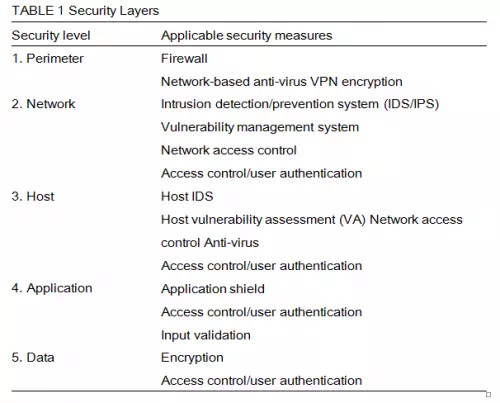

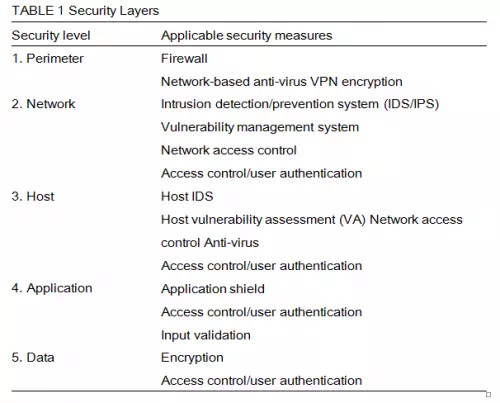

Ashley proposes five layers of security to be implemented in any network: Perimeter, Network, Host, Application, and Data. The layered approach requires a technical strategy to ensure implementation at different entries and levels across the network and an organizational strategy requiring participation of all network constituents (i.e., employees at all levels of the organization) (Ashley, 2006). Table 1 presents the functioning technologies in each of the security levels.

The physical infrastructure must also be secure. This includes a facility with various and diverse points through which an authorized user will enter. “Physical security should be looked at as a series of concentric perimeters, with each layer more secure than the previous one. What belongs in which circle depends on the value the corporation places on it” (Greene, 2004). It also includes employee training. According to a recent CompTIA survey, “companies with 25% or more of their staffs trained on security are 46.3% less likely to suffer a security breach” (Higbie, 2006). Social engineering is commonly used in attacks; therefore, properly training employees in secure strategies will greatly reduce their vulnerability and reduce the risk of an intrusion.

All aspects of security deployed in Ashley’s model, the physical security of the network facilities, and the education provided to the users are forms of layering and are essential to protect the network and the valuable data it houses.

Impeding

Hindering intrusion of unwanted and unwarranted users into and onto the network is essential to maintaining a secure environment. Impeding such attacks involves creating barriers, blocking unauthorized entry, and establishing boundaries for legitimate users by limiting access to network resources. “Limiting access to an application is generally divided into two topics: authentication, which is how an application identifies who you are, and authorization, which is how an application identifies what you [have] permission to do” (MSDN, 2009). Not every user should have access to everything. Allowing limited access to resources reduces attacks.

In addition, restricting user activity on the network helps to reduce network traffic. Implementing strategies such as reassigning priorities for print jobs or nonbusiness communications will allow relevant jobs to flow through the network without delay. Jobs with lower priority can wait for an opportune time to travel the network. Usually this is handled in seconds, so the end user is not aware of the holdup, but the network congestion and bottlenecks are greatly reduced (Hakala, 2008).

Impeding can also be applied to open ports on a system. On a desktop system, Windows File Sharing, Windows Messenger, and Windows Plug-n-Play services are open doors that are vulnerable to attacks. Software firewalls can be used to recognize when an application requests to open access to the system. If that request was not made by the user or a recognized application, the firewall can deny the request (JMU, 2009). Software firewall settings may, however, be modified by a user, leading to potential vulnerabilities in the effectiveness of that strategy, so additional measures may be necessary.

“Because attackers can observe Media Access Control (MAC) addresses of stations in use on the network, they can adopt those addresses for malicious transmission... station addresses, not the users themselves, are identified. That is not a strong authentication technique, and it can be compromised by an unauthorized party” (Kennedy, 2003). Kennedy suggests that by barring access to specific MAC addresses (filtered via a firewall), the overall security strategy of the network is improved. Though this technique is fallible since MAC addresses can be spoofed (or fooled) across the network, it is a common strategy found in network security plans.

Numerous vendors have developed tools to restrict access to systems, applications, and other network resources. HP Visual User Environment (VUE) identifies several techniques to limit access to the display, local file system, and system services. These are all handled through command line utilities. Cisco Systems has developed a method to limit the operating systems that can access the network using NAC Appliance. When users connect to the network, they are redirected to predefined login pages, depending on their operating system. Operating systems not configured for network access are denied.

As with layering, consideration must also be given to the physical security of the network. “No amount of firewalls, encryption or access lists can stop a criminal who gets into a server room” (Greene, 2004). Intruders who gain physical access to network resources can remove components quickly. In 2004, Bill Farwell, head of digital forensics at Deloitte Touche, admitted that he could remove a hard drive from a computer in less than five minutes. Since that time, mobile and portable devices are even more common, so the intruder needs only seconds to remove the desired equipment from the facility.

Diversity

“Diversity creates a natural firebreak for computers. I have never seen a virus that can infect both Linux and Windows boxes, and only a few can cross between Macs and PCs… diversity in computer platforms can prevent viruses from taking over” (Holtzman, 2003). Integrating various manufacturers, equipment, and security devices with different operating system platforms is an effective implementation of diversity on the network. Single-vendor solutions can create a weakness and points of failure.

Implementing a variety of access and authentication technologies (e.g., biometrics, barcodes, access keys) aids in strengthening security. “The application of security techniques (e.g., technologies, hardware and software manufacturers, passwords, traffic filters) that are different will ensure that intrusion at one layer will not guarantee further access by the same method” (Edge, 2008).

Recognizing that not all network environments have the resources to support numerous types of security hardware or network systems, other strategies can be implemented to apply the diversity principle in the security plan. Diversity can include a change in authentication at various levels within the system. It should also be included in the security plan of the physical facility, as simple as a different key used to access each lock-down device.

If hackers do penetrate one layer of the network, the plan is to keep them from proceeding. Diversity strategies impose such actions, discouraging further access. “The best containment strategy to avoid catastrophic failure is diversification” (Holtzman, 2003).

APPLICATION

Applying the SOLID principles to a security strategy is not always a clear-cut process. Many of the strategies span more than one principle and, depending upon how detailed each strategy or point is defined, may be categorized differently by other network security administrators. However, the following exercise is intended to demonstrate that all SOLID principles have been covered in the security plan.

Purdue University established a list of common best practices pertaining to system security (SecurePurdue, 2005). Though some of the points are specific to Purdue students/staff and the network supported for them, Table 2 demonstrates how those points can be implemented using the five security principles of the SOLID model.

The SOLID security principles can be applied to all types of networks. Andre Muscat, director of engineering at GFI, recommended a list of points to be considered

when developing a security plan for a network in which mobile devices are prevalent (MacKinnon, 2008). Table 3 shows how those strategies can be implemented using the five security principles of the SOLID model.

CONCLUSION

The implementation of the five security principles (Simplicity, Obscurity, Layering, Impeding, and Diversity) into any network will improve confidence that all reasonable measures have been taken to protect the network. Frequent review of the security plan is necessary to ensure the efficiency and effectiveness of the plan. The more frequent the application of each of the five principles defined in the SOLID model, the more reliable and solid the security of the system.

Irene E. Edge

Computer Technology,

Kent State University,

Ashtabula, Ohio, USA

Mark Ciampa, author of several network security textbooks, states: “Although you need many defenses to withstand attacks, you base these defenses on a few fundamental security principles: protecting systems by layering, limiting, diversity, obscurity, and simplicity” (Ciampa, 2005).

The author of this paper devised the acronym SOLID (Simplicity, Obscurity, Layering, Impeding, Diversity) from those principles to be used as an aid in designing, developing, and deploying a security strategy to confidently build a SOLID, secure network. The definition of the term solid includes “of good substantial quality or kind,” “thoroughly dependable,” “reliable,” and “serious in purpose or character” (Merriam-Webster, 2004). A network security administrator strives for a solid, impenetrable network. The acronym SOLID will serve as a model throughout the analysis, development, and implementation of a security plan. When reviewing the security strategies, the SOLID principles may be used in a checklist to determine the degree to which each principle has been applied in the security plan.

FUNDAMENTAL SECURITY PRINCIPLES

Examining the five network security principles individually will illustrate the importance of each. As each principle is explained throughout this article, the reader should strive to recognize strategies that relate directly to the network system being managed.

Simplicity

Simplicity is representative of how easy, or complex, it is to access the network. From the user’s perspective, the internal policies and procedures should not be too difficult to manage, thus preventing users from being productive in their daily tasks. In contrast, the network should be complex enough to ward off intruders. Network administrators must find the correct balance (unique to each situation) between blocking unwanted and unwarranted access to the network and providing the resources necessary to the authorized users of the network. “There is no such thing as ‘complete security’ in a usable system. Consequently, it is important to concentrate on reducing risk, but not waste resources trying to eliminate it completely. Such a pragmatic mindset provides a fighting chance to achieve fairly good security while still allowing productivity” (Avolio, 2009).

Establishing policies is critical to a secure network. One network security white paper on “best practices” states to create usage policy statements that outline users’ roles and responsibilities with regard to security: “This document should provide the general user community with an understanding of the security policy, its purpose, guidelines for improving their security practices, and definitions of their security responsibilities. If your company has identified specific actions that could result in punitive or disciplinary actions against an employee, these actions and how to avoid them should be clearly articulated in this document” (Cisco Systems, 2009). Education on the use of the system is extremely vital to the success of policy implementation. Another best practices article on wireless network security supports the same: “… develop institution-wide policies with detailed procedures …” and “conduct regular security awareness and training sessions for both systems administrators and users” (Kennedy, 2003).

An additional strategy that must be considered when implementing the simplicity principle pertains to default settings of hardware and software. In this case, the simplest thing to do is apply all of the default settings when installing new equipment or operating system and application software upgrades, but this is not necessarily done in the best interest of developing a secure network. Default settings often include password, encryption, and authorization settings that are known by anyone familiar with the same hardware or software. Therefore, though it takes a great deal of effort on the part of the technician to manage the new or improved system, changing many of those default settings will protect the system from hackers (Kennedy, 2003).

The SOLID principle of simplicity requires a security strategy responsive to all system functions. An unrestricted environment may allow faster processing but is not practical when handling confidential data. Hardening an operating system to the extent that the user is frustrated with each task submitted is also not a practical solution. A checks and balances system must be in place to weigh the simplicity and complexity of the network. Security measures should be taken that will not jeopardize user productivity.

Obscurity

WordNet defines obscurity as “the quality of being unclear or abstruse and hard to understand,” “not well known,” and “the state of being indistinct or indefinite for lack of adequate illumination” (Princeton, 2006). Obscurity may also be considered the “hidden” aspects of network security. Security by obscurity… represents one of the truly controversial aspects of security. You will often see mocking references to people whose efforts are dismissed as ‘just security by obscurity’” (Johansson & Grimes, 2008). Obscurity is used to lessen a risk or vulnerability by concealing the attack vector, thereby applying a reinforced measure of security to the system.

Examples of obscurity include renaming the administrator account to deter automated attacks and installing honeypots to act as decoys, enticing hackers away from the systems containing critical data. For a wireless network, changing the default Service Set Identifier (SSID) set by the manufacturer is important. The default SSID for Cisco wireless routers is “tsunami,” and the default SSID for Linksys wireless routers is “Iinksys.” A complex SSID naming convention should be defined and implemented to avoid easy access by an automated attack or an unauthorized user. The serious hacker may still be able to find a way around these security measures, but it does make the effort more difficult.

Included in obscurity should also be the avoidance of clear patterns of behavior, even to the point of random time settings for synchronizing systems across the network Consider a communication strategy used by the military in which a continuous signal of spurious transmissions is used to reduce the enemy’s detection of a serious communication when it is transmitted. Though spread spectrum techniques do not directly apply to the commercial domain, the implementation of clear behavioral patterns should be avoided.

The implementation of obscurity into the security plan is only one line of defense — not the line of defense — and is not to be measured but rather used as an early warning sign of exploitation. When such a barrier is breached, a potential and likelihood of a full-scale attack is amplified. This strategy may take some effort, but it is a principle that merits thoughtful consideration and periodic review to preserve the integrity and defense of the network.

Layering

Building layers of defense to protect digital assets is critical. Layering is implemented in the physical security plan as well as policy and administration. “Protecting your proprietary information does not require dozens of specialized solutions or unlimited funds. With an understanding of the overall problem, creating both a strategic and tactical security plan can be a straightforward exercise” (Ashley, 2006).

Ashley proposes five layers of security to be implemented in any network: Perimeter, Network, Host, Application, and Data. The layered approach requires a technical strategy to ensure implementation at different entries and levels across the network and an organizational strategy requiring participation of all network constituents (i.e., employees at all levels of the organization) (Ashley, 2006). Table 1 presents the functioning technologies in each of the security levels.

The physical infrastructure must also be secure. This includes a facility with various and diverse points through which an authorized user will enter. “Physical security should be looked at as a series of concentric perimeters, with each layer more secure than the previous one. What belongs in which circle depends on the value the corporation places on it” (Greene, 2004). It also includes employee training. According to a recent CompTIA survey, “companies with 25% or more of their staffs trained on security are 46.3% less likely to suffer a security breach” (Higbie, 2006). Social engineering is commonly used in attacks; therefore, properly training employees in secure strategies will greatly reduce their vulnerability and reduce the risk of an intrusion.

All aspects of security deployed in Ashley’s model, the physical security of the network facilities, and the education provided to the users are forms of layering and are essential to protect the network and the valuable data it houses.

Impeding

Hindering intrusion of unwanted and unwarranted users into and onto the network is essential to maintaining a secure environment. Impeding such attacks involves creating barriers, blocking unauthorized entry, and establishing boundaries for legitimate users by limiting access to network resources. “Limiting access to an application is generally divided into two topics: authentication, which is how an application identifies who you are, and authorization, which is how an application identifies what you [have] permission to do” (MSDN, 2009). Not every user should have access to everything. Allowing limited access to resources reduces attacks.

In addition, restricting user activity on the network helps to reduce network traffic. Implementing strategies such as reassigning priorities for print jobs or nonbusiness communications will allow relevant jobs to flow through the network without delay. Jobs with lower priority can wait for an opportune time to travel the network. Usually this is handled in seconds, so the end user is not aware of the holdup, but the network congestion and bottlenecks are greatly reduced (Hakala, 2008).

Impeding can also be applied to open ports on a system. On a desktop system, Windows File Sharing, Windows Messenger, and Windows Plug-n-Play services are open doors that are vulnerable to attacks. Software firewalls can be used to recognize when an application requests to open access to the system. If that request was not made by the user or a recognized application, the firewall can deny the request (JMU, 2009). Software firewall settings may, however, be modified by a user, leading to potential vulnerabilities in the effectiveness of that strategy, so additional measures may be necessary.

“Because attackers can observe Media Access Control (MAC) addresses of stations in use on the network, they can adopt those addresses for malicious transmission... station addresses, not the users themselves, are identified. That is not a strong authentication technique, and it can be compromised by an unauthorized party” (Kennedy, 2003). Kennedy suggests that by barring access to specific MAC addresses (filtered via a firewall), the overall security strategy of the network is improved. Though this technique is fallible since MAC addresses can be spoofed (or fooled) across the network, it is a common strategy found in network security plans.

Numerous vendors have developed tools to restrict access to systems, applications, and other network resources. HP Visual User Environment (VUE) identifies several techniques to limit access to the display, local file system, and system services. These are all handled through command line utilities. Cisco Systems has developed a method to limit the operating systems that can access the network using NAC Appliance. When users connect to the network, they are redirected to predefined login pages, depending on their operating system. Operating systems not configured for network access are denied.

As with layering, consideration must also be given to the physical security of the network. “No amount of firewalls, encryption or access lists can stop a criminal who gets into a server room” (Greene, 2004). Intruders who gain physical access to network resources can remove components quickly. In 2004, Bill Farwell, head of digital forensics at Deloitte Touche, admitted that he could remove a hard drive from a computer in less than five minutes. Since that time, mobile and portable devices are even more common, so the intruder needs only seconds to remove the desired equipment from the facility.

Diversity

“Diversity creates a natural firebreak for computers. I have never seen a virus that can infect both Linux and Windows boxes, and only a few can cross between Macs and PCs… diversity in computer platforms can prevent viruses from taking over” (Holtzman, 2003). Integrating various manufacturers, equipment, and security devices with different operating system platforms is an effective implementation of diversity on the network. Single-vendor solutions can create a weakness and points of failure.

Implementing a variety of access and authentication technologies (e.g., biometrics, barcodes, access keys) aids in strengthening security. “The application of security techniques (e.g., technologies, hardware and software manufacturers, passwords, traffic filters) that are different will ensure that intrusion at one layer will not guarantee further access by the same method” (Edge, 2008).

Recognizing that not all network environments have the resources to support numerous types of security hardware or network systems, other strategies can be implemented to apply the diversity principle in the security plan. Diversity can include a change in authentication at various levels within the system. It should also be included in the security plan of the physical facility, as simple as a different key used to access each lock-down device.

If hackers do penetrate one layer of the network, the plan is to keep them from proceeding. Diversity strategies impose such actions, discouraging further access. “The best containment strategy to avoid catastrophic failure is diversification” (Holtzman, 2003).

APPLICATION

Applying the SOLID principles to a security strategy is not always a clear-cut process. Many of the strategies span more than one principle and, depending upon how detailed each strategy or point is defined, may be categorized differently by other network security administrators. However, the following exercise is intended to demonstrate that all SOLID principles have been covered in the security plan.

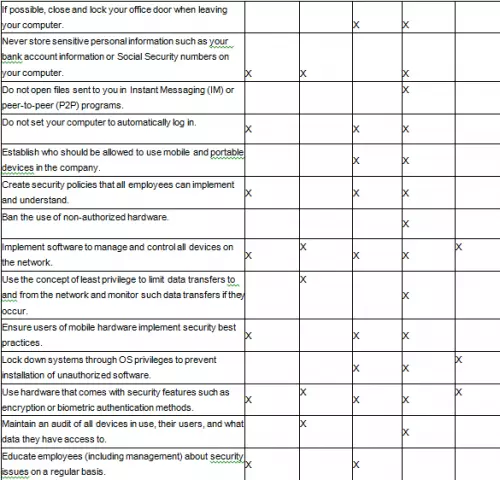

Purdue University established a list of common best practices pertaining to system security (SecurePurdue, 2005). Though some of the points are specific to Purdue students/staff and the network supported for them, Table 2 demonstrates how those points can be implemented using the five security principles of the SOLID model.

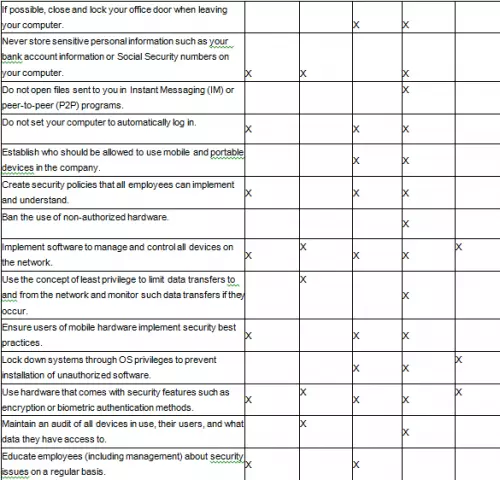

The SOLID security principles can be applied to all types of networks. Andre Muscat, director of engineering at GFI, recommended a list of points to be considered

when developing a security plan for a network in which mobile devices are prevalent (MacKinnon, 2008). Table 3 shows how those strategies can be implemented using the five security principles of the SOLID model.

CONCLUSION

The implementation of the five security principles (Simplicity, Obscurity, Layering, Impeding, and Diversity) into any network will improve confidence that all reasonable measures have been taken to protect the network. Frequent review of the security plan is necessary to ensure the efficiency and effectiveness of the plan. The more frequent the application of each of the five principles defined in the SOLID model, the more reliable and solid the security of the system.

Irene E. Edge

Computer Technology,

Kent State University,

Ashtabula, Ohio, USA

0 комментариев